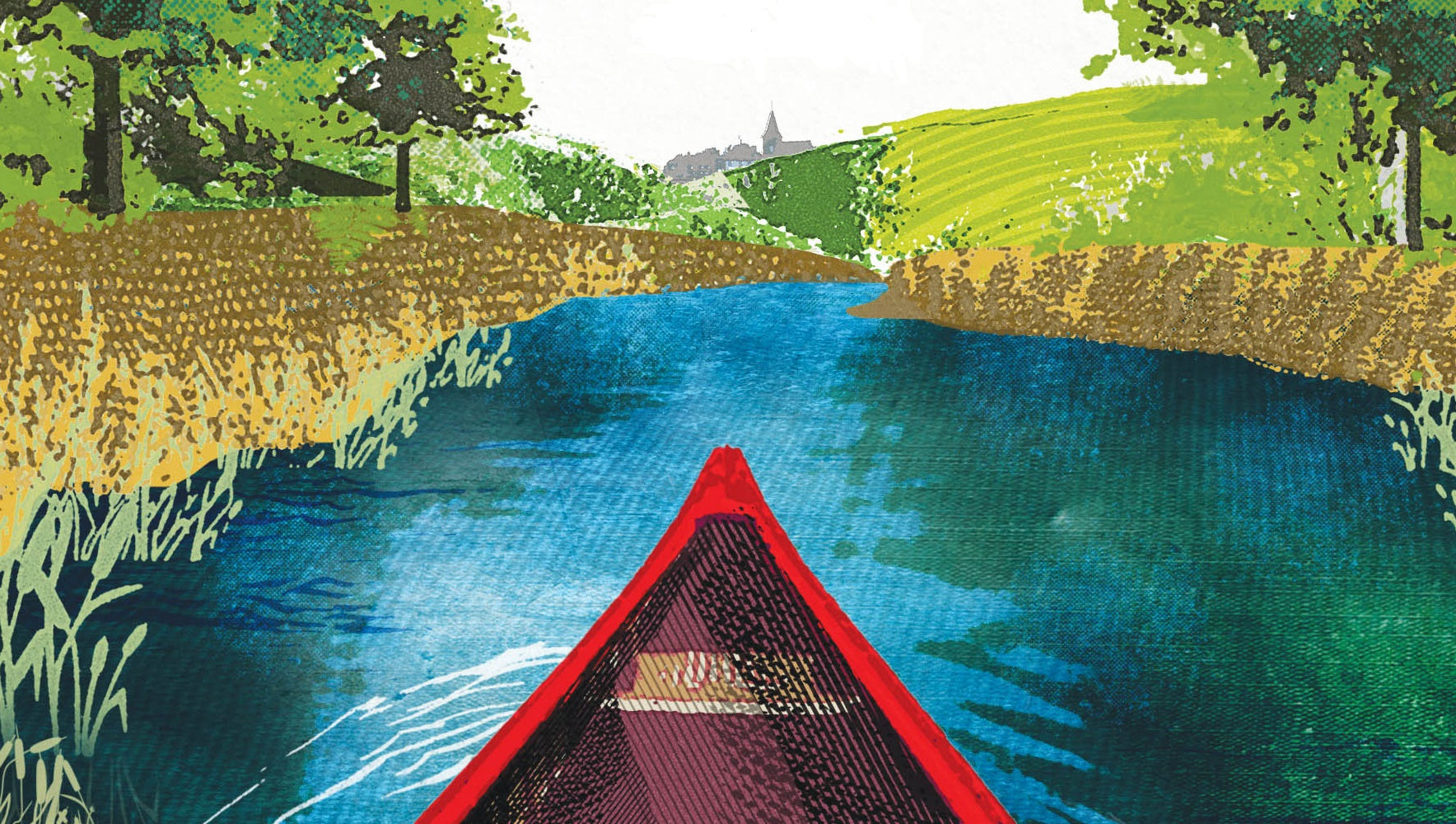

Microadventure in the middle of the Thames

This month's issue of Adventurous Ink, our regular dose of inky outdoor inspiration, is the rather wonderful 'Pull of the River' by Matt Gaw. An engaging travelogue of taking the slow route across Englands inland waterways in a Canadian canoe belonging to an old friend.

Here's an extract from Matt's time with Old Man Thames.

____

Downstream we slide alongside another eyot, the river’s silky skin wrinkling under the canoe. Two trees have fallen to create natural groynes, their branches raking the water to collect black silt that has formed a steep beach and a sheltered bay. We manoeuvre the Pipe in closer, the wash sucking and slapping onto the bank, and get out to explore.

The eyot looks ideal: densely packed with trees and scrub. A hideout. A refuge. A place to camp. The ground, perhaps recently underwater, is soft, and the tide has deposited bottles and cans in a muddy wrack line that extends some 30 feet from the bank. The island smells of bark, dead leaves and cold; winter is still thawing in the middle of the Thames.

Further in, through thorn and fallen branches, the island is firmer and tufted in soot-black moss, soft as fur. Poplars circle us, ivy tangling up straight trunks to brush leafless crowns. We pace between them, testing branches before deciding to string the hammocks up close together in front of an old ash. It’s a striking tree. Shaped like a stag’s head, bark hangs from its pronged branches like rags of half-shed velvet. There are treecreepers and bands of invasive parakeets, readying for roost.

The light had been fading on the river but the island is a place of perpetual gloom, the trees taking on the darkness of the Thames. We talk in low voices, settling into the surroundings, listening to the eyot’s sounds and becoming familiar with its movements, getting to know the lie of the land. The island is small but it is often hard to see the river through the trees. We are truly hidden. Removed from both land and water.

On the island there is a feeling of delicious, harmless naughtiness. These kind of spaces seem designed for pirates and parrots, schemers and plotters. We are the highwaymen of the high waters, intentionally marooned. I wonder when the last person stepped onto this island. Days ago? Maybe weeks? Perhaps it hasn’t been regularly visited since the great Frost Fairs between 1607 and 1814, when the Little Ice Age saw Old Father Thames freeze in his bed and whole towns assembled to skate and visit hastily erected shops and pubs. Ice many feet thick allowed Londoners to stride for miles across a riverscape transformed.

The biggest freeze came in the great winter between 1683 and 1684, when even the seas slushed with ice and froze solid for up to two miles from the shoreline. As in the Fens, the people of the Thames took to the river. The writer and diarist John Evelyn described how the ice was a scene of ‘bull-baiting, horse and coach races, puppet plays and interludes’, rife with ‘lewd places, so that it seemed abacchanalian triumph or carnival on the water’. He writes too of the ice’s impact on the land, how it

was a ‘severe judgement’ on the earth; the frozen sap of trees caused trunks to explode, splitting timber as ‘if lightning-struck’.

It has been over a century since the last big Frost Fair. The warming climate and the removal of the medieval London Bridge – whose closely spaced piers collected ice and helped dam the river’s tidal flow – brought an end to the big freezes. The last one of note was held for five days in 1814, when people danced reels to the sound of fiddles, while others gathered in drinking tents or sat by fires on the ice, warmed with rum and grog.

We return to camp; the buzz of life from the banks slips through the trees. Police sirens, a few shouts from early drinkers and the clumping whomp of swans coming into land. The shriek of the parakeets is gradually replaced by the soft tip-tap of rain on the tarps above us and the husky bark of a fox roaming the south bank. I imagine him, his nails clip-clipping along the Thames path, sniffing and rooting round bins, drinking in the scents of the human world that he has made his own. I snap on my torch to look for him, the red beam wobbling over the water to the bank. Empty. I turn it off.

Although the light in the eyot dims, darkness never really arrives at our camp. The glow from central London, still miles downstream, colours the sky orange like a sun that never quite sets; like a phosphorescent foxfire – the spooky light of fungi in decaying wood. It is the shimmering orange ghost of burning ancient forests and long-dead sea creatures.

___

Subscribe to Adventurous Ink in July, using the code INTROINK, to get Pull of the River completely free.