Why we now feature fiction, philosophy and poetry

Ten years.

That's how long I have been at this. I was 40 when I started, I'll let you do the math that's made a mockery of my hairline.

I've never liked worthy advice or worthiness in general, but, God, I was earnestly worthy back then.

'Know thyself.' Fail!

This isn't, however, about what I liked or knew, or didn't; no, it's a dawning realisation that my way of knowing was limited, which is why, until recently, I only featured nonfiction books.

To aim for the highest point is not the only way to climb a mountain

Nan Shepherd

It's not that I was oafishly unaware of beauty and the sublime. We've often featured eloquent, lyrical prose from the likes of Nan Shepherd, John Muir, Robert Macfarlane. Even, somewhat accidentally, esteemed poets such as Kathleen Jamie.

I will never recover from her withering "Well, I am Scotland's national poet" in response to my blundering enquiry about her verse poems whilst discussing her shimmering book Surfacing on the podcast (I note that this role is now referenced, at least in her Wikipedia page, if still not on her own website...)

However, for a long time, the subscription remained a rather rational affair; serious stuff with something important to say.

Eventually, inevitably, things began to change. I changed.

Alongside the books, I'd quit my day job and gone freelance, helping people and organisations move beyond the worthy veneer of sustainability to develop deeper, more regenerative practices and approaches.

I came to understand that it's the choices we make that shape the world, not the tools we then pick up and hack away with, and so became fascinated with our inner state.

I quit social media as best I could (possibly, two posts this year?) and plundered the World Of Books back catalogue, somewhat obsessively filling the social media shaped hole. I found books filled with possibility. A rich entanglement of science and spirituality unpicking our Western obsession with reason and logic, illuminating the power of our senses and the ability of language to arouse them.

I was catching on; it's not what you think, but how you feel that really matters. This is the pathos stuff that true storytellers instinctively get.

I've always looked for an emotional connection in our nature and adventure narratives, writers who can distil their experience down to its very essence, its most resonant meaning. So, when the right novel came along, it was a simple matter to nudge the nonfiction along to make space for something more speculative, richer in possibility and perspective; Richard Powers' epic The Overstory, followed by Manda Scott's powerful Any Human Power and Sarah Hall's breathtaking Helm.

Pathos isn't just about arousing the senses, though; it's about clearing space for the things we feel to really resonate, to reach our own conclusions.

All a leaf knows

about building a tree

is to turn towards the light.

When this line from poet James A Pearson woke me up with the electric tang of fresh firing synapses, I knew we had found our first full-blown book of verse, The Wilderness That Bears Your Name, one of the two books that featured in our first seasonal selection in 2024.

I realise there's a danger that this reads as 'old romantic discovers poetry - becomes a bit of a dick about it'.

But, seriously, I spent years working out that we needed to navigate between the worthy, the worthwhile and the wondrous. More trying to chart a path. I think I'm just about getting into my stride now.

Stories speak to us in an old way; they define our human experience, the spoken and unspoken. Which is why we have an innate need for them. It's only recently they became mere sideline, simple amusement. Which is not to say that enjoyment is somehow not important; we have to live life, not just think on it.

Our parables, folklore, and myths don't just entertain though; they are a deft device for sidestepping bullish thinkers and preachy writers with a certain flourish, firmly-footed on the primal floor; confident there is something deeper hefted in with the comedy and tragedy.

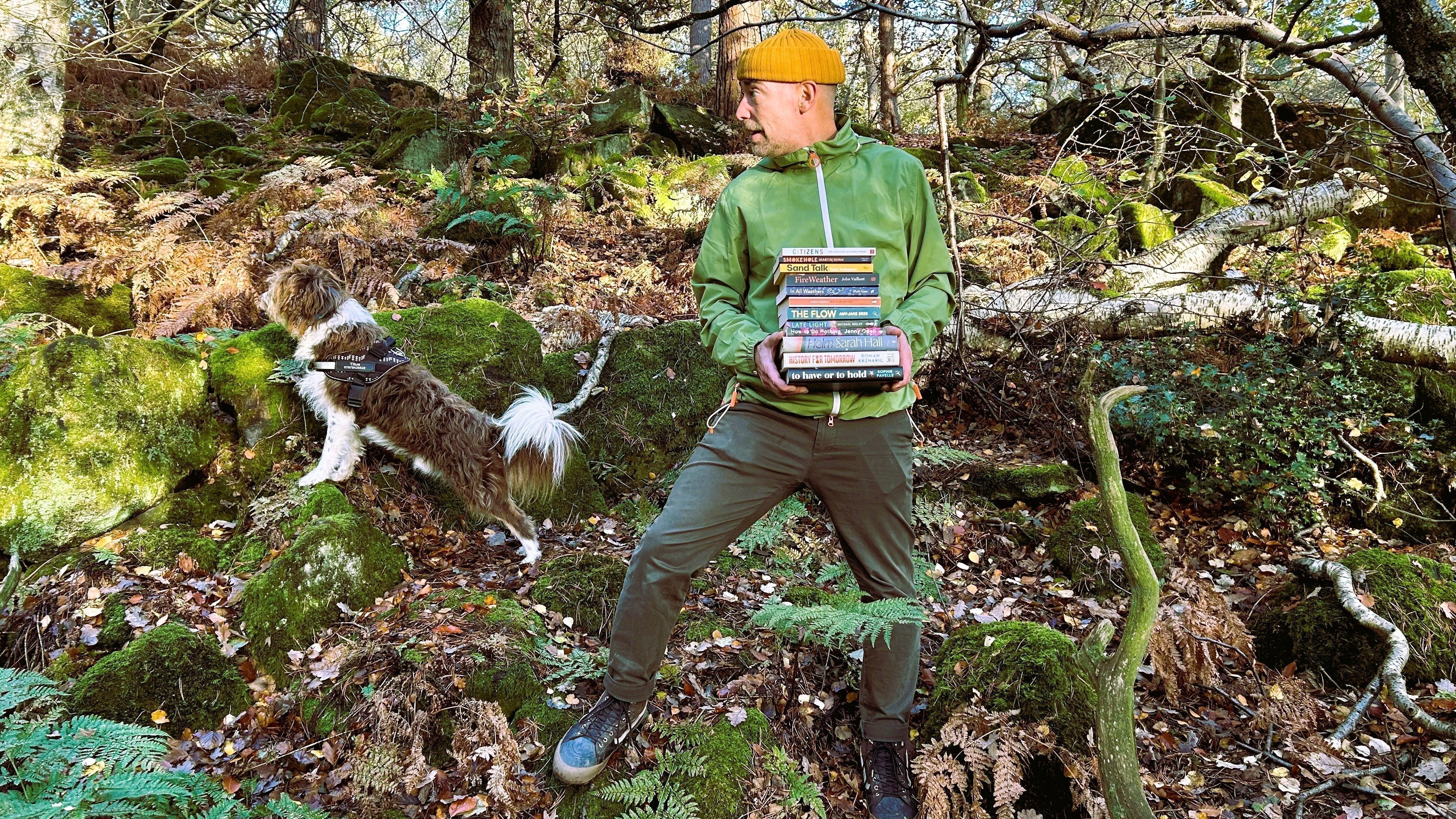

Whilst we may not sing the old songs anymore, there are still storytellers whose hearts ring with them. Having discovered his work, I waited patiently for the return of dark nights before featuring the writer and modern sage Martin Shaw. Look at him there, all sage-like. There's a man you'd wait for.

He is the first author we've ever featured with two books at once, sharing copies of Smoke Hole with our entire community, along with the darker, more demanding Courting the Wild Twin for our deep reads subscribers.

Martin has delved deep into his wild self, years under canvas, before returning to the world replete with new myths to grasp after the meaning. He has a compelling take on where we are.

There is no safe castle for us to return to; setting out for story is the only thing to do, the last hurl of the knucklebones left.

I have a terrible sense Martin is on the money there; 'No safe castle'.

This is a time, still the very beginning of a new millennium, that archaeologists and historians will one day ponder on when our machines no longer speak to them, weathered back to base mineral and ground underfoot.

But as long as there are humans, there will be stories and songs, poems and art.

Being part of it, 'setting out for story', is probably more important than we realise.

Get involved, choose your first book for free, or send a gift subscription.